Home > Recent Projects

Recent Projects

Recent Projects

Stillbirth Prevention

The SIDS Family Association Japan is embarking on a new project to help prevent stillbirth in Japan. Read below for background information about stillbirth in Japan and the research that is behind this project.

The Role of Fetal Movement Counting in Reducing Stillbirth

By Stephanie Fukui

The death of a baby through stillbirth is a painful, bewildering experience and an extreme trauma for any family. The cause of death is often undetermined and sometimes these deaths come with no warning.

However, sometimes there ARE warning signs before a stillbirth. Decreased fetal movement (DFM) is associated with increased stillbirth. There is agreement on this in the scientific community and recent studies re-confirm this [1]. At the same time, it has been observed in many instances that in populations where women are educated about DFM or asked to “count kicks,” the stillbirth rate decreases. It is logical therefore, to think that having pregnant women use kick charts to keep track of their baby’s movements in utero could be helpful and might help save lives.

The causes for DFM are many and researchers have only just begun to sort through the causes and then determine appropriate measures that should be taken when DFM is detected. Even more perplexing is the apparent fall in stillbirth rates that occurs simply by encouraging mothers to be vigilant about DFM. It is likely that years of research will be necessary to completely understand these issues as it has for finding the cause of SIDS and also SIDS’s relationship to back sleeping. Even after 20 years of research, the mechanism that causes a SIDS death is only just becoming clear and might eventually explain the relationship to back sleeping. Despite not having understood SIDS, campaigns to reduce SIDS deaths by reducing the SIDS risk factors were successful in reducing SIDS deaths by 50-70% in developed countries around the world. Therefore, even while researchers are working on scientifically explaining the relationship between DFM and stillbirth and the relationship between education on DFM and lower stillbirth rates, campaigns can be developed now to begin lowering stillbirth rates. Lives may be saved by distributing kick charts, educating women on how to count movements, and developing guidelines for care and management of these cases.

Kick/Movement Count

There are different methods to count baby’s movements which include kicks, jabs, twists, or rolls. One example is that mother is asked to be still in a laying or sitting position, roughly at the same time every day when the baby is USUALLY most active, and note the time it takes for for her to feel 10 movements within her womb. (This usually takes less than 15-20 minutes.) She records this time on the chart. She is to contact her OB provider promptly if she notices that it is taking longer than usual to feel the 10 movements. The good record can allow her to easily visualize a change from her baseline. She can bring the chart to her prenatal visits.

Can counting kicks influence the stillbirth rate?

There have been many studies done on various aspects of fetal movement counting and the results varied in terms of its role in the reduction of stillbirth. Accordingly, “kick count” has gained and lost and gained popularity over the years.

The Cochrane Collaboration reviewed studies written in English up until 2008 in order to try to determine whether kick counting helps in the reduction of stillbirth. Nine studies were thrown out because they were not scientifically rigorous enough. Four studies were included because they passed the litmus test for scientific rigor.

The Cochrane review concluded that “there is not enough evidence to recommend or not to recommend counting fetal movements.” It also states that “because of indirect evidence from these studies that fetal movement counting may be beneficial, more research is needed in this area.”[2] The indirect evidence is the observation that the stillbirth rate decreased in study populations where mothers learned of the importance of DFM, usually through distribution of Kick Charts [2, 3].

Since the Cochrane Review, there has been more such evidence reported along with data that shows that kick count is not harmful. Researchers in Norway designed an intervention that gave written information to all women at 17-19 weeks gestation about decreased fetal movement (including a kick chart that mothers could use as a tool) as well as guidelines for management of DFM for health-care professionals. Following more than 65,000 pregnancies and 4,200 reports of decreased fetal movements, they found that during the intervention the stillbirth rate fell by one third in the overall study population of singleton pregnancies and fell by 50% among women who reported DFM. There was no increase in the rates of preterm births, fetal growth restriction, transfers to neonatal care units or severe neonatal depression among women with DFM during the intervention. The use of ultrasounds increased, while additional follow up visits and admissions for induction were reduced. Also, the number of women presenting with DFM did not increase, so potentially harmful medical intervention did not increase [4].

Unanswered Questions

The relationship between decreased fetal movement and stillbirth has been established. The relationship between using kick charts and lower stillbirth rates has been observed. However, this observation cannot be interpreted. It is not known whether it is counting kicks that is helping to reduce the stillbirth rate or some other factor.

Also, if counting kicks is reducing the rate, it is not clear why such counting saves lives. For example, in a 1989 study and the largest one done to date, more mothers in the kick count group presented with live babies because of less movement, but these babies could not be saved because of falsely reassuring fetal testing. Yet, in this study, the stillbirth rate in both the counting group and the control group decreased [5]. The Norway study mentioned above showed that the kick count group did not wait as long to contact the doctor and the number of ultrasounds increased. However, there was not an increase in babies transferred to neonatal unit [4]. So even though there were less stillbirths when using kick charts, how babies were saved is not understood.

Japan

Every year in Japan there are almost 4000 stillbirths. (This is defined as a loss after 22 weeks of gestation and represents a rate of 3.4 per 1000 pregnancies.)[6]

Compared to some other developed countries, Japan’s stillbirth rate is low. This can be attributed to universal health care where virtually every woman gets care from early pregnancy, extensive use of ultrasound as a tool at each check up, some awareness of DFM and in some cases distribution of kick charts.

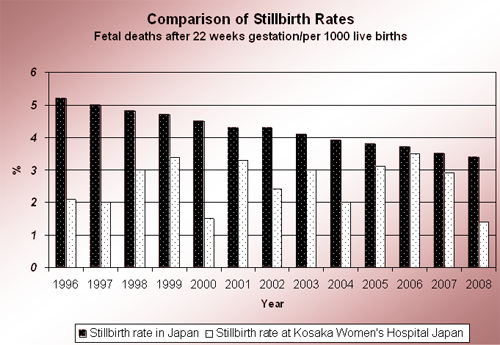

It is estimated that perhaps 80% of hospitals in Japan warn mothers of decreased fetal movement. There are a few hospitals in Japan where mothers are asked to keep track of baby’s movement using a kick chart. Emphasizing the importance of DFM by distributing pamphlets and kick charts could be making the stillbirth rate even lower. Data over a 12-year period in one hospital in Japan that distributes kick charts (Kosaka Women’s Hospital run by Dr. Hideo Takemura) shows that this hospital’s stillbirth rate is below the national average [7].

Table 1: The stillbirth rate at Kosaka Hospital compared to the overall rate of Japan.

The graph above shows that the stillbirth rate at Kosaka Women’s Hospital, where kick charts are distributed, has been lower than the national average for the past 12 years. The rate at Kosaka Hospital looks more erratic because of the small number (about 2000 births per year) compared to the number of births nationwide. Though there might be other factors influencing the low stillbirth rate at Kosaka Hospital, this is one more case that supports the observation that kick charts are associated with lower stillbirth rates. Note that the stillbirth rates shown above for Kosaka Hospital do not include the stillbirth Moms who transferred into the hospital and who may not have used kick charts.

U.S.A.

First Candle, a group that supports research and bereaved families in the U.S., has done a thorough review using experts from outside and within their organization. They concluded that the epidemiological evidence is strong enough to warrant starting a stillbirth prevention campaign with a pamphlet and public service announcement (funded by The Heinz Foundation) in 2008 in selected cities. This campaign is now being expanded. The brochure explains kick count and includes a kick chart for mothers to use.

See their website for details:

http://www.firstcandle.org/new-expectant-parents/kicks-count/

Pros and Cons of Using Kick Charts

There are arguments for and against using Kick Charts.

- Against: Some have suggested that keeping a daily kick count chart may not be necessary since the stillbirth rate in the Grant study fell in both the counting and control study populations and that could have been because of more awareness of DFM in both groups [5]. It is possible that just increased vigilance by doctor, an “informal inquiry of movements” when mother comes for her checkup to monitor baby’s movements is enough.

- For:Even if kick count charts are not essential for a campaign to reduce stillbirth, kick charts (plus explanation brochure) are a sure way to truly get pregnant women educated on this topic. They are a simple, pragmatic tool that teaches mothers to be vigilant every day and the charts help them see patterns as they come to better understand their baby's movements. (Though women who do not want to keep the chart should not be pressured to do so.) “Informal inquiry of movements” could be misinterpreted by medical professionals and could end up being skipped or deemed unimportant.

As mentioned above, data from Japan shows that a hospital distributing kick charts enjoys a lower stillbirth rate than the national average. It has been observed that health care providers sometimes ask questions about fetal movement in a vague manner, such as "How is the baby moving?" or "How much is your baby moving?" at prenatal appointments. The information they get back is not particularly good or useful. These kinds of questions might also confuse parents. A kick chart would provide specific (and perhaps life-saving) information on each baby. The brochure handed to parents would help to educate them and clear up any concerns. - Against: Keeping charts could put pressure on mothers or make it feel like the happy process of pregnancy has been “medicalized.”

- For:Pregnant women who do not want to keep kick charts should not be pressured to do so. Studies have confirmed that counting does not produce anxiety in mothers [5, 11].

- Against: Any campaign would need to be very cautious with wording because just as laying baby on the back does not prevent all SIDS, kick charts cannot prevent all stillbirths. In many cases, death of the baby cannot be prevented even if there is early detection of less movement and mother goes to hospital sooner. For example, a genetic problem may preclude death, or even cord accidents can be difficult to prevent.

- For:Campaigns could be very careful with wording and careful not to make false claims

- Against: An “alarm limit,” the number of kicks that might indicate a serious problem, has not been established clearly. Generally in the studies so far, 10 kicks within two hours has been used as the lowest limit of normal. However, several studies, including a Japanese study, found that 10 counts in 10-15 minutes might be more normal [8]. Therefore, alarm limits or thresholds are unknown and in fact may vary widely depending on individual babies. Also, the best method of counting kicks has not been established.

- For:We do know that any noticeable decrease in movements is important and even without established alarm limits or counting methods, a kick chart would identify any significant change such as a decrease in movement. Brochures for kick count written so far have suggested that the kick chart is a good way for mother to find what is “normal for her baby.” There may be no need (and it may be impossible because of individual differences) to establish thresholds that apply to everyone.

- Against: It has been suggested that mothers who detect decreased movements will come to clinics more often and have expensive medical tests that are not necessary.

- For:Kick charts are a simple and inexpensive way to monitor babies. There are no monitoring devices or lab tests required! More detection of decreased movement might increase office visits but it did not do so in the Norway study mentioned above where the number of women presenting with DFM did not increase when the kick charts were distributed, though the stillbirth rate DID DECREASE [4]. Even if office visits and testing does increase, our goal is to prevent stillbirth whenever possible so more expense may be necessary.

When presenting with DFM, the next challenge is to figure out which tests are effective in determining the problem so that only necessary tests are given. In the above-mentioned study, of the women presenting with DFM, the ultrasound rate increased. Therefore there was a shift toward ultrasound as an assessment tool and good management of these cases probably made a difference. In the past, falsely reassuring fetal tests and substandard management of these cases have prevented doctors from saving some babies [9]. Finding ways to better manage high risk pregnancies is essential. Early detection of Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR), etc. seems to be important; one Swedish study showed that undetected FGR led to a deteriorated outcome whereas those that were detected while still in the womb fared better [10].

Other Possible Benefits of Kick Charts

There are other possible arguments for kick charts and its benefits:

- Maternal vigilance of fetal movement can decrease delayed presentation to the health care facilities and thus may allow more timely intervention (4).

- Doctors often feel they cannot gather enough information on each baby because they see the pregnant mother only once a month and just for a few minutes. Kick charts can provide the doctor with more detailed information on baby. Also, when the mother brings in her kick chart every month, this gives her a chance to talk in more detail to the doctor thereby making kick charts the cause of forming closer relationships and having better communication with doctor and medical staff [12].

- Fetal movement counting increases the mother’s involvement and lets her take more responsibility for her own prenatal care. It might be that the reason counting does not produce anxiety in mothers is that mothers are excited about their new baby and enjoy recording their baby’s movements. They may also feel they are mothering and protecting their baby by being involved in this way.

- By spending less than half an hour each day to be still and pay attention to her baby, kick charts promote acute awareness of body and of baby by mother. This could also encourage psychological bonding to baby.

- Kick count charts kept by pregnant women could give us important data that would provide directions for further research.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Drs. Shigeki Matsubara, Hideo Takeuchi and Toshimasa Obonai for their valuable contributions to this report. Thanks also to Kathleen Graham, Dana Kaplin, and Dr. Diep Nguyen

References

- Froen JF: Management of Decreased Fetal Movements. Elsevier Seminars in Perinatology 2008: 32:307-311.

- Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ: Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007: (1):CD004909. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com

- Froen JF: A kick from within--fetal movement counting and the cancelled progress in antenatal care. J Perinat Med 2004: 32(1):13-24.

- Holm Tveit JV, Saastad E, et al. Reduction of late stillbirth with the introduction of fetal movement information and guidelines - a clinical quality improvement. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009: 9(32).

- Grant A, et al. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risks of antepartum late deaths in normally formed singletons. Lancet 1989: 2:345-347.

- Mother’s and Children’s Health and Welfare Association, Maternal and Child Health Statistics of Japan 2009.

- Takemura H: Symposium Abstracts, Stillbirth cases that were not predicted. Onwa Society Newsletter 2006: No. 88.

- Kuwata T, Matsubara S, et al. Establishing a reference value for the frequency of fetal movements using modified ‘count to 10’ method. J.Obstet.Gynaecol.Res 2008: Vol 34, 3:318-323.

- Froen JF: Fetal Movement Assessment. Elsevier Seminars in Perinatology 2008: 32:243-246.

- Lindqvist PG, et al. Does antenatal identification of small-for-gestational age fetuses significantly improve their outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005: 25:258-264.

- Liston RM, et al. The psychological effects of counting fetal movements. Birth 1994: 21-135.

- Takemura H: Counting Movements: A Signal from Baby! The Japanese Journal of Perinatal Care 1996: 185:86-88.